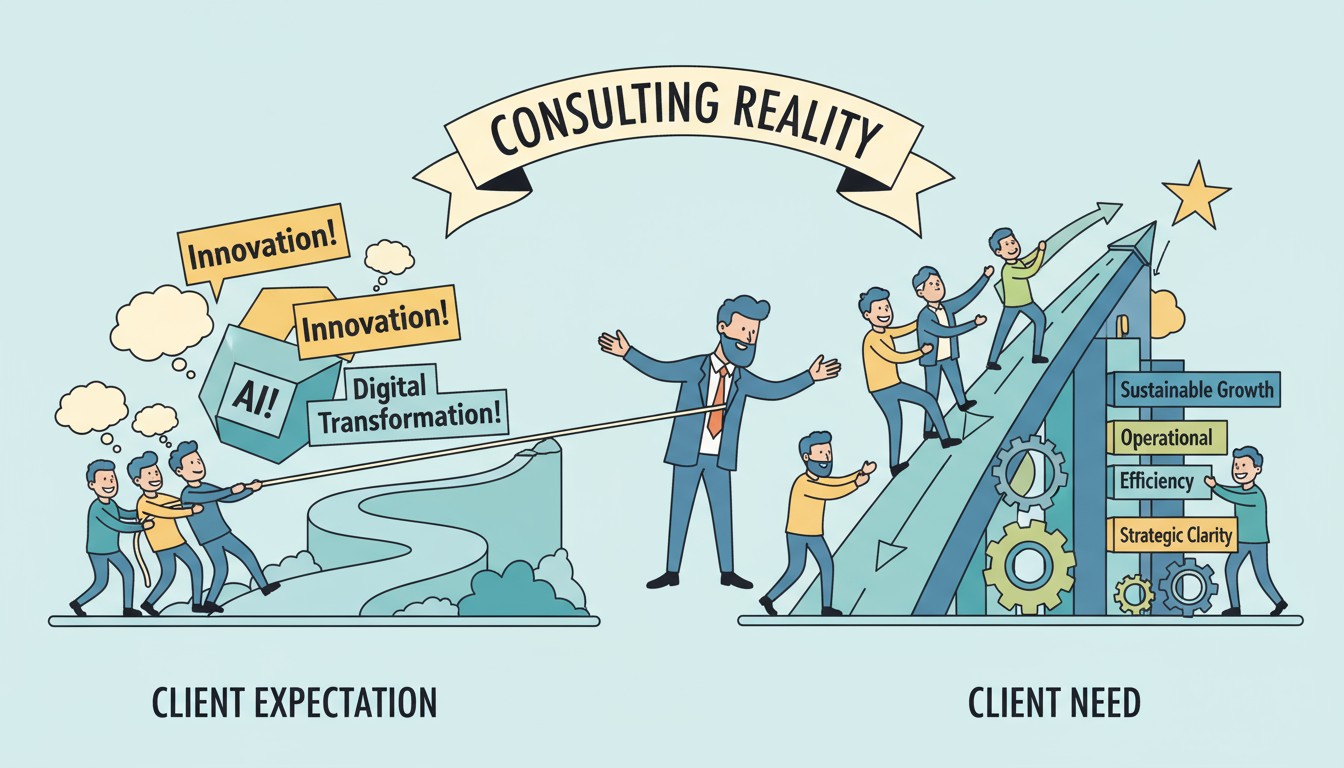

When clients engage consultants to solve business problems or capitalize on opportunities, they typically arrive with clear ideas about what they need, expressed through specific requests for particular deliverables, methodologies, or solutions that seem obviously appropriate from their perspective based on how they understand their situations. However, experienced consultants recognize that these initial requests frequently represent symptoms of deeper underlying issues rather than accurate diagnoses of root causes, or they reflect solutions the client already decided upon without properly analyzing whether those solutions actually address the fundamental problems creating the challenges they experience. This disconnect between what clients initially request and what actually would benefit them most creates what we might call the expectation gap, which represents one of the most challenging dynamics that consultants must navigate skillfully to deliver genuine value rather than simply providing whatever clients ask for regardless of whether those requested deliverables solve the actual problems.

Let me guide you through the psychology, business dynamics, and practical realities that create this expectation gap, explaining why intelligent capable business leaders so often misdiagnose their own situations despite living within them daily, how consultants can identify the real needs hiding beneath surface-level requests, and what approaches work for redirecting engagements toward addressing actual problems rather than simply executing against initial briefs that may or may not serve client interests effectively. My goal involves building your understanding of this fundamental consulting challenge deeply enough that you can recognize expectation gaps in your own work, develop strategies for surfacing hidden needs that clients themselves may not consciously recognize, and navigate the delicate interpersonal dynamics involved in telling clients that what they asked for differs from what they actually need without damaging relationships or appearing arrogant about understanding their business better than they do themselves.

Why Smart People Misdiagnose Their Own Problems

Think about why business leaders who successfully built companies, managed complex operations, and made countless good decisions over years or decades would suddenly prove unable to correctly identify what problems need solving when they engage consultants for help. This seeming contradiction becomes less mysterious when you understand the cognitive and organizational factors that systematically distort how people perceive problems they are embedded within compared to how external observers with fresh perspectives analyze those same situations. The issue has nothing to do with intelligence or capability but rather involves predictable psychological patterns that affect everyone regardless of how smart or experienced they are when trying to diagnose situations they participate in actively rather than observing objectively from outside.

Consider the forest versus trees phenomenon where people immersed in daily operational details lose ability to see larger patterns that external observers identify immediately. When you spend every day managing specific processes, resolving immediate crises, and responding to urgent demands, your attention naturally focuses on those concrete tangible elements directly in front of you rather than stepping back to examine whether the entire system design makes sense or whether you are optimizing details within a fundamentally flawed overall approach. Imagine someone meticulously organizing filing cabinets and implementing sophisticated document management procedures when the real problem is that their business generates far too much unnecessary paperwork that should be eliminated entirely rather than organized more efficiently. From inside the situation focusing on daily document management tasks, optimizing the filing system seems like the obvious solution. From outside observing the broader business model, the consultant immediately recognizes that better filing does not address why so much paperwork exists in the first place.

Organizational politics and ego protection create additional layers of misdiagnosis because admitting certain types of problems would be professionally or personally embarrassing in ways that make alternative explanations psychologically more comfortable even when those alternatives do not accurately reflect reality. A senior executive whose poor leadership decisions created employee morale problems leading to retention challenges will unconsciously prefer framing the situation as needing better compensation structures or enhanced benefits programs rather than acknowledging that their leadership style drives people away. The compensation framing allows them to request consultant assistance on a respectable technical problem while avoiding the uncomfortable self-reflection that recognizing leadership issues would require. Similarly, departments that failed to implement processes correctly prefer diagnosing problems as technology limitations requiring new systems rather than admitting they never properly adopted the adequate systems already available, because blaming technology protects them from acknowledging their own implementation failures.

The solution-before-problem pattern represents another common misdiagnosis mechanism where clients become enamored with particular solutions they encountered through conferences, articles, or peer discussions, then retrofit problems to justify implementing those appealing solutions regardless of whether those solutions actually address their most pressing challenges. You observe this frequently with emerging technology trends where executives return from industry conferences excited about artificial intelligence, blockchain, or whatever current buzzword dominates discussion, then instruct their teams to find ways to implement these technologies within their operations. The resulting consultant engagements focus on deploying the predetermined solution rather than analyzing what problems most urgently need addressing, frequently resulting in expensive implementations of sophisticated technologies that solve problems nobody actually had while ignoring the unglamorous operational issues that truly constrain business performance.

Common Patterns of Request Versus Actual Need Mismatches

After working with dozens or hundreds of clients across various industries and situations, consultants begin recognizing recurring patterns where specific types of requests consistently mask different underlying needs that emerge through diagnostic work revealing what actually drives the challenges clients experience. Understanding these common patterns helps you develop hypotheses early in engagements about what might truly be needed versus what clients initially requested, allowing you to structure discovery processes that efficiently test these hypotheses rather than blindly accepting stated needs without investigation. Let me walk you through several archetypal patterns that appear repeatedly across consulting engagements in ways that illustrate the systematic nature of expectation gaps rather than representing random isolated misunderstandings unique to particular situations.

The strategy request masking execution problems represents perhaps the most frequent pattern where organizations request help developing strategies, conducting market analyses, or creating business plans when their actual problem involves inability to execute existing strategies they already developed but never properly implemented. Think about why this pattern emerges so consistently across different clients and industries. Creating strategy feels intellectually satisfying and appears to represent sophisticated leadership thinking about markets, competition, and positioning, while acknowledging execution failures feels like admitting organizational incompetence at basic operational management. Additionally, organizations genuinely convince themselves that their execution struggles stem from strategy inadequacy rather than implementation discipline, reasoning that if the strategy were better then execution would naturally improve. The consultant brought in to develop new strategy quickly discovers through diagnostic interviews that the organization has three previous strategic plans sitting on shelves collecting dust, each containing reasonable approaches that were never seriously attempted much less properly implemented before leadership gave up and commissioned yet another strategy refresh hoping this new version will somehow inspire the execution discipline that previous strategies failed to generate.

The technology solution request hiding people and process dysfunction follows similar patterns where clients request help selecting and implementing technology systems when the real issues involve organizational culture, change resistance, or process design flaws that no technology can fix regardless of how sophisticated or expensive. The classic example involves companies requesting new enterprise resource planning systems or customer relationship management platforms while treating technology selection as the primary challenge, when investigation reveals that their current systems possess adequate functionality that was never properly configured or adopted because people refused to change working habits established before those systems existed. The organization spent millions on technology sitting mostly unused while employees maintain parallel shadow systems using spreadsheets and email precisely because nobody addressed the human and process dimensions that determine whether technology implementations succeed or fail regardless of the technical capabilities the systems theoretically provide.

The organizational restructuring request concealing leadership effectiveness problems follows similar dynamics where companies frequently reorganize reporting structures, create new divisions, or consolidate departments hoping that different organizational charts will resolve issues that actually stem from specific leaders being ineffective in their roles or senior executives failing to communicate clearly across existing structural boundaries. Restructuring allows leadership to appear decisive and action-oriented while avoiding the uncomfortable conversations required to address individual performance issues or their own communication shortcomings. The consultant analyzing the situation discovers that the organization has restructured multiple times over recent years without resolving persistent coordination problems because the structural changes never addressed the real issue that certain key executives simply refuse to collaborate effectively regardless of where boxes sit on organization charts.

The Discovery Process That Reveals Hidden Needs

Skilled consultants approach early engagement phases with healthy skepticism about whether stated problems accurately reflect actual needs, structuring discovery processes that test initial diagnoses rather than immediately accepting client assertions about what needs fixing. This investigative approach requires balancing between respecting client intelligence and experience with recognizing that external perspectives often reveal patterns invisible to internal participants too close to situations to perceive them objectively. Think about how doctors conduct examinations rather than simply prescribing whatever treatments patients request based on self-diagnosis from internet searches. Good doctors listen respectfully to patient descriptions of symptoms and concerns while simultaneously conducting independent examinations that may reveal entirely different conditions than patients suspected, because medical training provides diagnostic frameworks and pattern recognition that patients lack despite knowing their own bodies intimately.

The consultant discovery process typically begins with comprehensive stakeholder interviews that deliberately include perspectives beyond whoever initially engaged the consultant, because limiting conversations only to the engagement sponsor creates echo chambers where you hear only the diagnosis that person already formed without testing it against how others throughout the organization perceive the same situations. When a chief executive requests strategy development, interviewing direct reports often reveals that execution challenges rather than strategy inadequacy represent the actual constraint, because those closer to implementation observe execution failures firsthand while the executive only sees that results fall short of expectations without direct visibility into why implementation consistently falters. Similarly, when department heads request new technology systems, interviewing end users frequently exposes that current systems would work adequately if properly configured and adopted, but nobody invested effort to train users or customize systems to match actual workflows rather than theoretical ideal processes that look good on paper but clash with operational reality.

Real Discovery Example: The Strategic Planning That Revealed Cultural Dysfunction: Consider an engagement where a rapidly growing technology company requested help developing a three-year strategic plan because their CEO believed unclear strategy caused coordination problems between departments that kept launching conflicting initiatives without apparent alignment. The consultant began with standard strategic planning methodology including market analysis and competitive positioning work that the CEO expected, but simultaneously conducted extensive interviews with department heads and middle managers to understand how strategic decisions currently got made and communicated.

These interviews revealed a completely different story than strategy inadequacy. The company actually had reasonably clear strategic direction that the CEO communicated regularly through all-hands meetings and strategy documents accessible to everyone. However, the CEO also had a management style of constantly generating new ideas and casually mentioning them in conversations without clearly distinguishing between serious strategic pivots versus brainstorming thoughts he was testing verbally. Department heads interpreted every casual CEO comment as a directive requiring immediate action, launching initiatives based on these offhand remarks while the CEO remained unaware people were treating his informal musings as formal strategic changes. The real problem had nothing to do with strategy quality or clarity but rather involved the CEO’s communication patterns combined with a culture where people felt afraid to ask clarifying questions about whether casual comments represented actual strategic direction or just exploratory thinking. The consultant redirected the engagement from strategic planning toward helping the CEO develop more disciplined communication practices distinguishing between formal decisions and informal brainstorming, combined with culture work helping the organization develop comfort with asking clarifying questions rather than assuming every executive comment requires immediate action. This fundamental redirection only became possible through discovery interviews that revealed how strategy actually got interpreted and implemented rather than simply analyzing strategy documents and assuming the stated request accurately reflected the underlying need.

Process observation and data analysis complement interview insights by providing objective evidence about how work actually flows through the organization compared to how people describe it during conversations. Interviewees naturally present somewhat idealized versions of processes during discussions, describing how things are supposed to work or how they work on good days rather than the messy reality of typical operations including all the workarounds, exceptions, and informal coordination mechanisms that keep things functioning despite official processes being inadequate. Shadowing employees through their actual work routines reveals these gaps between espoused and actual processes, often exposing that requested solutions address symptoms rather than root causes. When clients request better project management tools, observation frequently shows that the existing tools work fine but people ignore them because unrealistic planning assumptions make official schedules meaningless, causing everyone to operate based on informal networks and constant verbal coordination rather than trusting the project management systems that contain fiction rather than realistic workable plans.

The Delicate Art of Redirecting Expectations

Discovering that client needs differ from their requests creates challenging interpersonal dynamics because telling someone they misunderstood their own problems risks appearing arrogant or dismissive while potentially triggering defensive reactions that damage consultant credibility and relationships regardless of how accurate the alternative diagnosis might be. Think about how you would react if a consultant you hired to help with a specific problem announced after preliminary work that you completely misunderstood your situation and actually need something totally different from what you requested. Even if intellectually you recognize that external perspectives provide valuable insights, emotionally you might feel the consultant is criticizing your judgment or questioning your competence to understand your own organization, creating resistance to accepting their alternative framing regardless of supporting evidence they present.

Skilled consultants manage this delicate redirection through approaches that validate client perspectives while introducing new information and interpretations gradually rather than bluntly contradicting initial diagnoses. The key involves framing discoveries as building upon client insights rather than rejecting them as wrong, because even when clients misdiagnose root causes they typically correctly identify symptoms and consequences even if they misattribute those symptoms to incorrect causes. When a client requests strategy development because they observe coordination problems between departments, acknowledge that coordination issues definitely exist and represent real business constraints, then present evidence showing that these coordination problems stem from communication pattern issues rather than strategy clarity problems. This framing validates that the client correctly identified a genuine problem worth addressing while redirecting toward more effective solutions that address actual root causes rather than symptoms.

Building shared understanding through collaborative discovery rather than delivering conclusions as expert pronouncements helps clients internalize new perspectives because they participate in analyzing evidence and drawing conclusions rather than simply receiving consultant assertions about what problems really are. Instead of presenting interview findings through formal reports declaring that technology needs differ from client assumptions, facilitate working sessions where client teams review interview themes and discuss patterns they observe, guiding them toward recognizing insights through their own analysis rather than being told what those insights should be. This facilitated discovery approach takes longer than simply telling clients what you concluded but proves far more effective for actually shifting perspectives because people believe conclusions they reach themselves far more readily than identical conclusions presented by outsiders regardless of how much evidence supports those external assertions.

When Clients Resist Redirection and Insist on Original Requests

Sometimes despite consultants presenting compelling evidence that actual needs differ from stated requests, clients resist redirection and insist on proceeding with originally requested work even when both parties recognize those deliverables will not address root problems effectively. This resistance stems from various factors including organizational politics where the engagement sponsor committed to specific deliverables they must produce regardless of whether those deliverables prove useful, budgetary constraints where funds were approved for particular scope that cannot easily be changed without revisiting approval processes, or psychological investment where changing course feels like admitting the initial diagnosis was wrong in ways that threaten professional ego or credibility with colleagues who were told the consultant would address specific issues.

Think about the ethical and practical dilemmas this resistance creates for consultants who recognize that proceeding with requested work provides limited value while potentially preventing addressing actual needs that would benefit the client substantially more than delivering requested but ultimately ineffective solutions. On one hand, clients are paying for consulting services and have the right to decide what work they want done even if consultants believe alternative approaches would serve them better. Additionally, consultants who insist too aggressively on redirection risk being perceived as difficult or unwilling to deliver what clients purchased, potentially damaging relationships and future business opportunities. On the other hand, delivering work you know will not actually help the client raises questions about professional integrity and whether you are truly serving client interests or simply collecting fees for producing deliverables regardless of their utility.

The resolution approach skilled consultants adopt involves documenting the redirection recommendation through formal communications that clearly state what actual needs were discovered and what alternative approaches would better address those needs, then if clients still insist on original scope, proceeding with requested work while incorporating elements addressing real needs wherever possible within the constraints of approved scope. This documentation serves multiple purposes including protecting consultant reputation if the engagement ultimately proves ineffective because you have written record showing you recommended different approaches that were declined, creating potential future opportunities to revisit the underlying needs after delivering initial scope and building trust through honoring commitments even when you disagree with the direction, and ensuring organizational memory beyond the immediate engagement sponsor so that when leadership changes or time reveals that original approach did not solve problems, documentation exists explaining what alternative recommendations were made.

Within the constraints of proceeding with requested scope despite recognizing it does not address root needs, look for opportunities to subtly incorporate elements that do address actual problems through the way you frame analysis, the recommendations you embed within requested deliverables, and the questions you pose during working sessions that plant seeds for future recognition of underlying issues even if they cannot be addressed within current engagement parameters. When delivering the requested strategic plan that you know execution problems will prevent from being implemented, include implementation planning and accountability frameworks within the strategy document itself that at least creates foundation for addressing execution discipline even if the client primarily wanted the strategy content rather than implementation systems. This approach of doing what was requested while finding creative ways to address what was needed demonstrates commitment to genuine client service rather than simply collecting fees for delivering whatever was purchased without regard for whether it actually helps.

Building Long-Term Relationships Through Addressing Real Needs

The consultants who build lasting client relationships generating ongoing engagements and strong referrals are invariably those who develop reputations for identifying and addressing actual needs rather than simply delivering whatever clients initially request. Think about why clients would continue engaging consultants who primarily serve as order-takers executing against stated requests without questioning whether those requests actually address important problems. While some clients might value consultants who do what they are told without challenging assumptions, most sophisticated clients recognize greater value from advisors who bring independent thinking and sometimes uncomfortable insights that improve outcomes even when those insights require changing direction from initial plans.

Consider the long-term trajectory where initial engagements successfully deliver requested scope but do not actually improve business performance because they addressed symptoms rather than root causes. The client relationship often ends after that initial engagement because the client perceives the consultant failed to deliver meaningful value despite technically completing all stated deliverables, and they have no interest in engaging someone who produced work that did not help even though the consultant properly executed against the agreed scope. Conversely, when consultants successfully redirect engagements toward addressing actual needs and those focused efforts produce genuine business improvements, clients recognize the consultant provided wisdom beyond just technical execution, creating foundation for trusted advisor relationships where the consultant gets engaged early in problem-solving processes to help diagnose needs before jumping to solutions rather than being brought in late to execute against predetermined solutions that may or may not be appropriate.

The transition from transactional consultant executing against specific projects to trusted advisor engaged in ongoing strategic partnership typically requires successfully navigating multiple instances where you helped clients discover that their initial problem framing needed adjustment, then demonstrating through results that the redirected approach delivered superior outcomes compared to what originally requested work would have achieved. This track record of accurately diagnosing situations and steering toward effective solutions builds confidence that your perspective adds genuine value beyond just execution capabilities, making clients receptive to involving you earlier in their thinking processes rather than only engaging you after they have already decided what needs to be done and simply need help implementing predetermined solutions.

Teaching Clients to Diagnose Their Own Problems More Effectively

Beyond addressing expectation gaps in individual engagements, sophisticated consultants invest effort in helping clients develop better diagnostic capabilities themselves so that future problem-solving starts from more accurate assessments of what actually needs addressing rather than repeatedly requiring external consultants to redirect misdiagnosed situations. Think about how this capability building serves both client interests and consultant business development in complementary ways. Clients benefit from improved internal ability to identify and frame problems appropriately, reducing wasted effort on ineffective solutions and enabling them to engage external expertise more productively when needed because they can articulate problems clearly rather than requesting solutions before properly understanding underlying issues. Consultants benefit because clients who understand problem diagnosis better become more sophisticated buyers of consulting services who appreciate the value consultants provide through insight and analysis rather than just seeking lowest-cost execution of predetermined solutions.

Teaching diagnostic thinking involves making your analytical processes transparent rather than presenting only conclusions, because when clients observe how you approach problem diagnosis they can learn those methods and apply them independently to future situations. During discovery phases, explain why you are conducting particular analyses or asking specific questions rather than just doing the work and reporting findings. For example, when interviewing stakeholders beyond the engagement sponsor, explicitly explain that getting diverse perspectives tests whether problems look the same from different organizational vantage points versus representing one person’s interpretation that others might not share. When analyzing process flows, describe how you distinguish between espoused processes documented officially versus actual workflows people follow in practice, because this distinction often reveals where problems truly occur despite official processes appearing adequate on paper.

Diagnostic Framework Worth Teaching Clients: Let me share a practical diagnostic framework that helps clients move from jumping to solutions toward properly analyzing problems before deciding what interventions might be appropriate. The framework involves three sequential questions that force disciplined thinking about problem characteristics before evaluating potential solutions. First, what observable symptoms indicate a problem exists, and can those symptoms be measured objectively rather than just described qualitatively? This forces specificity about what exactly is not working rather than vague assertions that things are not as good as they should be. Second, what are three different plausible explanations for why those symptoms occur, deliberately generating multiple hypotheses rather than settling on the first explanation that seems reasonable? This counteracts confirmation bias and solution-before-problem thinking by requiring consideration of alternative explanations before committing to particular diagnoses.

Third, what evidence would distinguish between these competing explanations, and how can we efficiently gather that evidence before deciding which hypothesis best fits reality? This prevents endless analysis paralysis while ensuring some investigation occurs before jumping straight from symptoms to solutions without testing whether assumed causes actually create observed effects. Teaching clients this framework through applying it collaboratively during engagements then explicitly discussing how the framework shaped your analytical approach gives them a reusable mental model for future problem-solving that improves their diagnostic accuracy even when consultants are not involved. Organizations that internalize this disciplined diagnostic thinking waste far less effort pursuing solutions to misdiagnosed problems, creating cultures that value understanding before acting rather than confusing motion with progress by implementing solutions without properly verifying those solutions address actual root causes rather than just symptoms or imagined problems.

The Deeper Purpose of Consulting Beyond Delivering Scope

The expectation gap between what clients request and what they actually need reflects the fundamental value proposition that distinguishes truly excellent consulting from mere technical execution of predetermined tasks. Anyone can follow instructions and produce deliverables that match stated requirements, but genuine consulting wisdom involves recognizing when stated requirements miss the mark and helping clients discover more effective approaches even when those discoveries require uncomfortable conversations about misdiagnosed situations. This higher-level value creation demands courage to challenge client assumptions respectfully, skill at facilitating shared discovery rather than imposing external expert opinions, and commitment to client success measured by actual business improvement rather than by whether deliverables technically satisfied original scope regardless of their ultimate utility.

The consultants who achieve lasting success and build reputations as trusted advisors rather than interchangeable service providers are invariably those who master the delicate balance of respecting client intelligence and organizational knowledge while bringing fresh external perspectives that reveal patterns invisible from inside situations. This requires developing both the analytical capabilities to diagnose problems accurately through systematic investigation and the interpersonal sophistication to help clients accept insights that may challenge their initial understanding without triggering defensive reactions that prevent effective collaboration. Understanding expectation gaps as natural inevitable features of consulting work rather than unfortunate exceptions helps you approach every engagement with appropriate diagnostic skepticism about whether stated needs accurately reflect actual problems, while maintaining the humility to recognize that sometimes clients do correctly diagnose their situations and your role simply involves helping implement solutions they already identified appropriately. The art involves distinguishing between these situations through disciplined discovery processes rather than assuming either that clients always know best or that they always misdiagnose, because both extremes prevent the nuanced adaptive thinking that effective consulting requires for serving diverse clients facing genuinely different situations requiring customized rather than formulaic approaches.

Disclaimer: This article provides general educational perspectives about common consulting dynamics and client relationship patterns based on experiences consultants frequently encounter across various industries and engagement types. Actual consulting situations vary enormously based on specific client circumstances, organizational cultures, problem characteristics, and interpersonal dynamics that make every engagement unique despite certain recurring patterns discussed here. The frameworks and approaches presented represent general guidance rather than prescriptive formulas guaranteed to work in all situations, because effective consulting requires adapting methods to specific contexts rather than mechanically applying standardized techniques regardless of situational nuances. This content does not constitute professional consulting advice, project management guidance, or organizational development recommendations tailored to any particular situation. Consultants must exercise independent professional judgment in determining appropriate approaches for their specific engagements, and clients should evaluate consultant recommendations critically rather than accepting assertions uncritically regardless of how confidently presented. The examples and scenarios discussed represent composites and generalizations rather than descriptions of any specific actual client situations, and any resemblance to particular organizations or engagements is coincidental rather than intentional. Neither the author nor publisher assumes liability for consulting outcomes, client relationships, or business results that may occur through attempting to apply concepts discussed in this general educational content without appropriate consideration of specific situational factors that materially affect what approaches will prove effective in particular circumstances.